What do I really know about China? I know there’s a lot of good food, only the tip of which I have experienced here in New York City (I believe everyone who has been there and attests that the food in China changes everything you thought you knew about Chinese food.) I’ve seen a lot of dramatic films recounting tales of dynasties and cultural revolutions. I know there are serious human rights issues to contend with, notoriously profiled around the Beijing Olympics but stretching past that in every direction. I know that the Chinese have made their mark on development throughout the Asian and African continents. I know there’s a rich cultural history, from tea to literature to art.

What I don’t know a lot about is the art and everyday life that don’t make the headlines. I’ve been able to glimpse some of that through independent documentaries, like Last Train Home and Up the Yangtze – films that shed light on major societal issues through the lens of ordinary individuals – and Disorder.

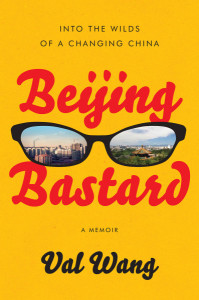

I imagine the latter film is in the vein of the film that made Val Wang excited about going to Beijing in the late 90s. In her recent memoir, Beijing Bastard: Into the Wilds of a Changing China, Wang writes about her journey to and through Beijing, where she had gone to immerse herself in the underground cultural scene, meet extended family and produce something creative along the way. She was inspired by an underground documentary she had seen in college (Beijing Bastards), and when she arrives in Beijing, she is faced with a changing city, shedding itself of some of its old trappings.

I was excited to read her memoir because it gives the reader a portrait of China that is far different from the mainstream stories we usually get. She befriends Yang Lina, whose documentary Old Men captures the lives of old men sitting on the sidewalk through four seasons. “The documentary had consecrated a completely nondescript spot on the sidewalk, though the old men were no longer there,” she writes. “Through her film I was seeing a side of the rapidly changing city that was hidden in plain sight. It offered me one of the deepest understandings I had of the city yet.” And this is what Wang’s book does for me.

We follow her daily life, the small moments of making friends, working, partying, and discovering the city. But it feels so much larger, as you realize that like in every changing society, these experiences will never happen in the same way again. In the way that cities gentrify and change, in the way that certain energies are pushed aside in favor of the shiny and new. It’s a story we see over and over in our own communities. Wang cherishes the idea of the old – the hutongs, the courtyard houses of her elders, the divey hair salons, the local (bao) seller – some of which represent the China that her parents left. She’s not finding her roots per se. She’s very adamant about that. (Her taxi driver: “So you’ve come back to China to xun gen.” To search for your roots. Wang: “No, I’m not coming back to China. I’m not from here. I’m American. And I’m not coming here to xun gen…I’m coming here to xun…Maoxian.” Adventure.)

But she is searching a bit for the China that her parents left, and, unknowingly at the time, trying to make sense of their life choices. But those things are fast disappearing, and as the city she lives in is shifting into something else, so too is she – into a different pace, with a refined view of what she wants her own life to encompass.

As a docuphile, I’m keenly interested in her quest to meet the underground documentary filmmakers and to pursue her own film. She gets a job writing at an English-language newspaper, and uses her position to interview artist and filmmakers. She meets the maker of the titular film and many of the filmmakers in his network. She is eager to learn how to become a filmmaker, how to tell stories.

One of the filmmakers, Zhang Yuan, instructs on stories (“China is a great place to be a writer because here is where the craziest stories in the world are.”) and documentary (”Do you know the secret to being a documentarian?…To be kuanrong and to use lixing.” Tolerant and rationality.)

Another, Wu Wenguang, talks with her about seeking freedom. She writes: “I laughed when he said I needed my freedom but something about it stuck in my craw. It was an inner state that we all sought, no matter what system we lived in. This was the voice I’d been waiting for, someone who would tell me to let go of other people’s ideas for me and to follow my own, not just about making a documentary but about everything. I needed someone to say that I could be anything I wanted to be in life, and mean it.”

She begins to make her own way, to take on Beijing and embrace it, creating a world in which she is happy and free from the expectations of her Chinese-immigrant parents in the states. That freedom, of course is ironic. She says to another newspaper editor, “I know what I like most about being here. Freelancing…freedom in general. I feel really free here.” She writes: “John started laughing. ‘You’re from the United States of American and you come to the last huge Communist country in the world to find freedom,’ he said, with a combination of pity and admiration that somehow pleased me.”

We follow her as she gets to know a family of Peking-opera performers, training her camera on them in hopes of a documentary film. We get to see the ordinary processes of making art and film – production, the struggles of inspiration, networks and egos, day jobs and trying to make day jobs something you actually want to do. And through it all, we observe the maturity and transformation Wang passes through as her previous judgments of her family and culture are softened, her perceptions better understood.

Wang’s voice is fresh and humorous, self-deprecating just enough to still be charming. We go along this journey with her in Beijing, until she applies for a writing program and prepares to leave China. Has she accomplished what she set out to do? “I hadn’t infiltrated the inner circle of Falun Gong leaders or taken up the cause of any political dissident or exposed any humiliating government scandals. Nothing important had happened to me in five years. I’d been a hunzi, befriended a few artists, failed to make a documentary. How could you write about that?” But she could, and she did. And gives us a new picture of alternative Beijing that helps us understand a bit more the complex country and society that is China.

– Karen Cirillo